Finding the First Life-Saving COVID-19 Treatment: The Untold Story

On the 16th June 2020, the first proven life-saving COVID-19 treatment was found. Approximately 650,000 lives will be saved over the course of 6 months due to this discovery - almost 16 times the UK death toll.

On the 16th June 2020, the first proven life-saving COVID-19 treatment was found. Dexamethasone was found to reduce COVID-19 deaths by over a third (35%) for those on ventilation and a fifth (20%) for those on oxygen therapy.

Approximately 650,000 lives will be saved over the course of 6 months due to this discovery - almost 16 times the UK death toll. The drug is cheap, widely available and can be produced as a generic - offering a life-saving tool in countries where social distancing simply is not an option.

Seemingly, researchers in every country around the world had tried in desperation to be the first to find the breakthrough; yet a British Government-funded clinical trial, led by Oxford University in National Health Service hospitals had won the race.

A nation, seemingly one of the worst affected in the world, had achieved what no one thought possible. This was no accident though, and this article seeks to tell the untold story behind this achievement.

Securing Medicine Supply

On the 25th February 2020, the British Government began quietly adding potential COVID-19 treatments to a list of medicines that were banned from hoarding and parallel export from the UK. This initially included drugs like Lopinavir-Ritonavir, Chloroquine and Azathioprine - on the 13th March 2020, this was expanded to include hydroxychloroquine. Of 198 medicines currently on the list, only 29 were added prior to the first known case of COVID-19 in the UK.

Such restrictions do not ban export of medications specifically; but place restrictions on activities like hoarding and "parallel export" which are ordinarily used by pharmaceutical companies to restrict medicine supply for making further profit. In the case of parallel export, this utilises EU Single Market rules to import medication into one country in the EEA (European Economic Area) and then sell them on for a higher price elsewhere. Academics in Poland have found this EU policy is responsible for pan-European medication shortages, particularly in Eastern Europe.

The UK Government obtained legal power to impose such bans through its withdrawal from the European Union; The Human Medicines (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 allowed the UK Government to unilaterally place bans on hoarding and parallel export. Such powers were originally created to prevent any possibility of medicine shortages after Brexit, but were re-purposed. These measures weren't at the expense of other countries, but benefited everyone by helping secure global drug supply by curtailing pharmaceutical giants.

These steps weren't simply taken to allow the UK to secure medicine supply should effective treatment be found, but instead for the UK to play a decisive role in finding the first treatment.

Treatment with Pseudo-Science

During the start of the pandemic, doctors around the world tried in desperation to save lives using any and all drugs which were reported to help, regardless of whether the reality was they were causing harm or benefit.

A report from Italy found kidney injury to two COVID-19 patients who were overdosed with Vitamin C as part of a cocktail of drugs used to attempt to "treat" them:

Nevertheless, we acknowledge that our patients received kidney biopsy several days after the resolution of Covid-19 and with already no SARS-CoV-2 RNA detectable by RT-PCR on oropharyngeal/nasal swab. Our report is then not able to rule out a potential role for SARS-CoV-2 in generating initial tubular injury, but at the same time, it provides no elements to suggest it.

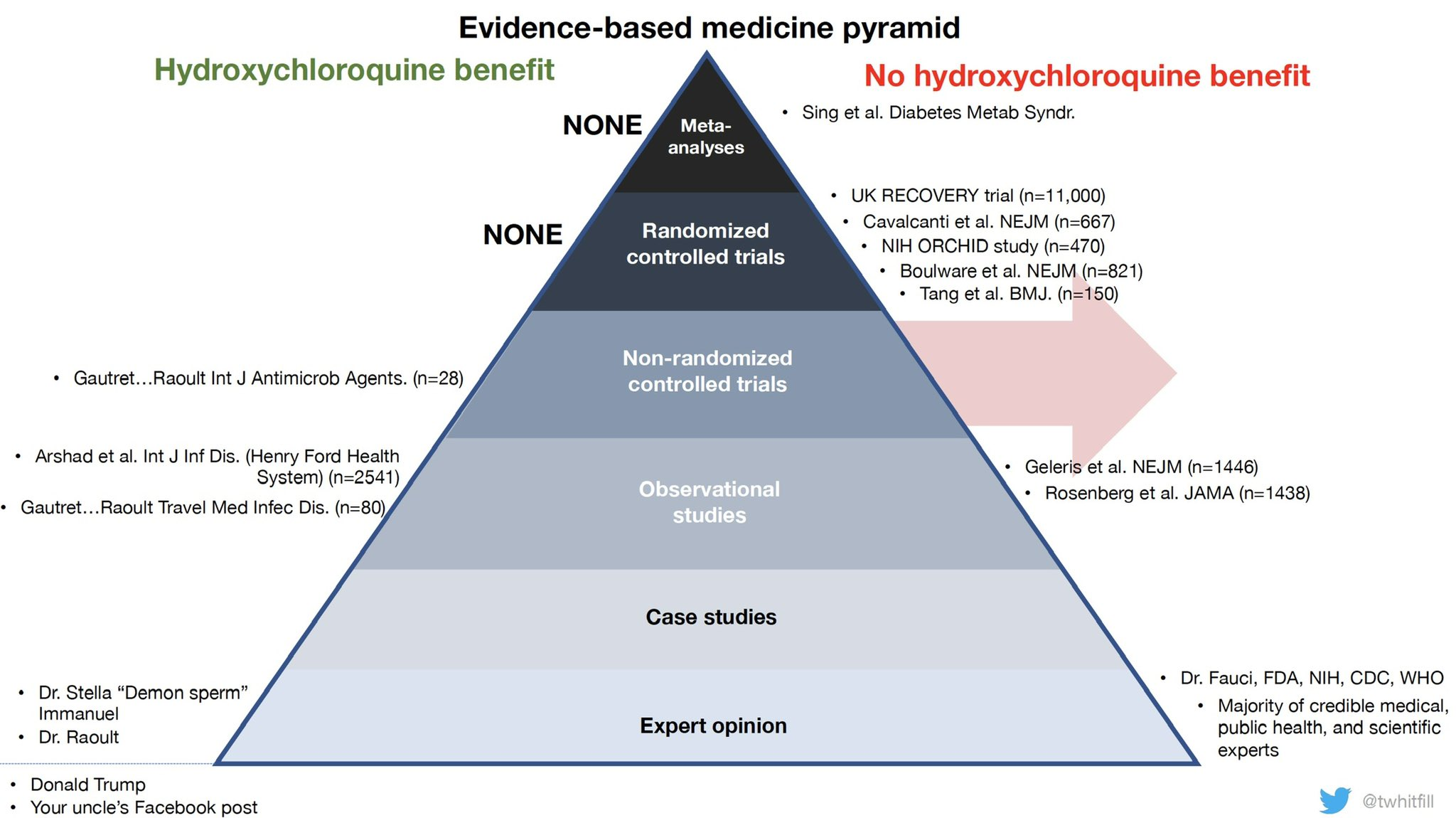

The Gold Standard mechanism for treatment evidence is through large-scale RCTs (Randomised Control Trials). National leaders in countries like France, the United States, Brazil, etc flocked to using drugs like hydroxychloroquine without such evidence being in place. At the same time, papers claiming to show harm from using hydroxychloroquine were based on poor retrospective studies with no randomisation (and are now retracted). Doctors in challenging situation used such drugs out of desperation.

Study into anti-inflamatory drugs like dexamethasone was further curtailed by the French Health Minister, Olivier Véran, declaring on Twitter that such drugs could be dangerous on the basis of no real evidence.

The RECOVERY Trial

In running clinical trials, the UK has a key advantage; a centrally controlled socialised healthcare system known as the National Health Service, provided free for all at the point of use.

The Chief Medical Officers of all four nations of the United Kingdom put particular emphasis on recruiting into clinical trials and preventing the use of drugs on an off-label basis; in one letter they wrote:

The results are essential to the future treatment of UK and global patients. We will ensure important results are disseminated rapidly to improve practice.

The faster that patients are recruited, the sooner we will get reliable results. While it is for every individual clinician to make prescribing decisions, we strongly discourage the use of off-licence treatments outside of a trial, where participation in a trial is possible. Use of treatments outside of a trial, where participation was possible, is a wasted opportunity to create information that will benefit others. The evidence will be used to inform treatment decisions and benefit patients in the immediate future.

Any treatment given for coronavirus other than general supportive care, treatment for underlying conditions, and antibiotics for secondary bacterial complications, should currently be as part of a trial, where that is possible.

Under such conditions, a single trial run by two professors at Oxford University has so far recruited 12,224 patients over 176 NHS hospitals. By contast, the World Health Organisation's flagship SOLIDARITY trial has only recruited 5,500 patients over 39 countries.

This decision directly demonstrated the UK Government's commitment to finding treatment, over simply attempting to reduce the Case Fatality Rate within its own borders. With off-label treatment banned, the UK faced one of the worst Case Fatality Rates in the world, but the resulting research saved far more lives globally.

The RECOVERY Trial identified potential treatments using expert opinions on potential treatments. On the 30th March 2020, researchers from King's College London and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust published a paper claiming that dexamethasone alleviated COVID-19 inflammation in mice. Despite claims by international health organisations advising against the use of corticosteroids, the authors claimed there was no robust scientific evidence supporting such viewpoints.

Results

So far, the RECOVERY Trial has results for three drugs. The first results came in for hydroxycloroquine, finding no benefit (and potentially a risk of harm). This results have now been replicated by numerous other clinical trials (unfortunately, due to the public attention on hydroxycloroquine, much research effort globally was spent on running trials for that one drug). After the RECOVERY trial posted results, emergency authorisation was quickly revoked globally, including by the US, France, Italy and Belgium. The WHO discontinued study into the drug in its SOLIDARITY trial.

The RECOVERY Trial then moved to more positive news - finding the benefits of dexamethasone. Following a press release, the results are now published in The New England Journal of Medicine. The drug is used off-label by doctors around the world and official medical guidelines have been updated:

- As the results were posted, the UK CMOs approved use

- Quickly after, the WHO welcomed results

- The US NIH updated treatment guidelines to include dexamethasone

- Specific approval granted in countries like Japan, Taiwan and South Africa

Unfortunately, the EU's Medicines Agency have only just begun reviewing the drug for EU-wide approval, but individual countries and doctors are already using the drug at scale.

Finally; the RECOVERY trial found no benefit for Lopinavir-Ritonavir. Whilst negative results are useful in preventing harm to patients, they nevertheless come with some disappointment. Whilst the RECOVERY trial continues to explore further drugs, it is unlikely results will come quickly as the increase in patients in COVID-19 patients has stalled. Nevertheless, the RECOVERY trial stands ready should there be a second wave in the winter.

Conclusion

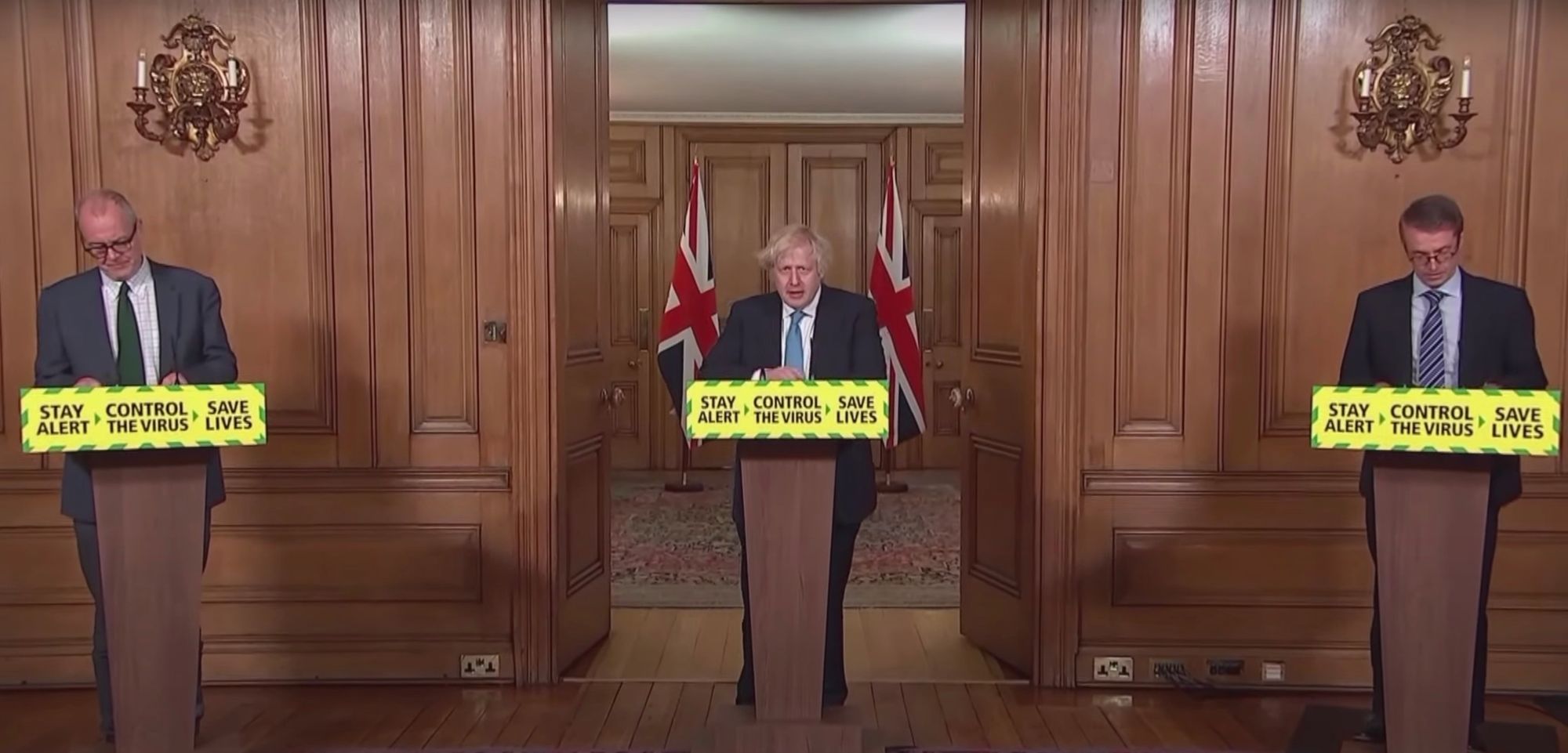

The British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, announced the breakthrough at the second-to-last of the regular daily Coronavirus Press Briefings. Approaching the podium at the start, the Prime Minister looked first to his left, and then to his right.

Towards his right was, Sir Patrick Vallance, the Government Chief Scientific Adviser who was no stranger to these press briefings. To his left was a new face to these briefings, Professor Peter Horby, Co-Chief Investigator of the RECOVERY Trial.

This was not a discovery by superheroes. Professor Peter Horby got into medical school after getting a B, C & D grades at his A Levels. His fellow Co-Chief Investigator, Professor Martin Landray, earned his medical qualifications from Birmingham University and is not publicly known to be part of any Government scientific committees. Life saving results came from a clinical trial, powered by NHS clinicians throughout the UK and patients who volunteered in extreme circumstances. Ordinary people, who sacrificed so much to save the lives of others - whose stories will never likely be widely known.

Whilst dexamethasone became the first proven life-saving treatment for COVID-19 in the world, another, a far more expensive drug is also around. Peter Horby also served as co-investigator on a trial that found an anti-viral drug called remdesivir (developed US pharmaceutical company, Gilead) could shorten treatment time of patients though with no benefit to mortality.

Further good news may be coming soon though - initial trials by Synairgen (a biotech company in Southampton) and the University of Southampton within Southampton NHS hospitals found that a new drug, SNG001, reduced the chance of severe disease by 79% versus a placebo and no patients died in the treatment group. Treatments are just one piece of the puzzle, and this piece won't cover the huge efforts involved in vaccine research.

Nevertheless; there is a significant philosophical dilemma at the core of this - research into treatments (and vaccines for that matter) require patients. When, at your disposal, you have a nation with the scientific funding, centralised healthcare system and scientists to achieve medical breakthroughs that can save hundreds of thousands of lives globally; is it ethical to refuse a degree of self-sacrifice?

In the meantime, I will leave you with the words of Tyler Cowen from a Bloomberg Opinion piece on the UKs COVID-19 response:

It is fine and even correct to lecture the British (and the Americans) for their poorly conceived messaging and public health measures. But it is interesting how few people lecture the Australians or the South Koreans for not having a better biomedical research establishment. It is yet another sign of how societies tend to undervalue innovation — which makes the U.K.’s contribution all the more important.

Critics of Brexit like to say that it will leave the U.K. as a small country of minor import. Maybe so. In the meantime, the Brits are on track to save the world.